An extract from ‘Modern Myths and Medical Consumerism – The Asclepius Complex’ (Routledge, 2018)

By Antonio Karim Lanfranchi

In Greek and Roman mythology, Apollo had the power not only to cure human diseases and wounds, but also to inflict them. On the one hand he was the solar principle of life and knowledge, the basis of order and symmetry, god of the arts, medicine, music and prophecy. On the other hand he could strike at the human world anywhere with his unerring bow, and was therefore the ‘cause’ of all sickness and pestilence. According to a Roman oracle, only he who had caused a disease had the power to cure it, and that was Apollo himself. Medicine, therefore, is a quintessentially Apollonian art.

Apollo the physician was the father of Asclepius. The story of the latter’s birth is told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Asclepius was born of Apollo’s love for Coronis, a mortal woman of royal blood. Apollo fell in love with her when he saw her bathing on the shore of a lake in Thessaly. After they had consummated their passion, he left the crow, whose feathers were white at the time, to watch over her. Soon afterwards, encouraged by her father Phlegyas, king of the Lapiths, Coronis married Ischys. The crow flew to Apollo to tell him about it. The god was so furious that he turned the bird’s plumage black to punish it for not keeping Ischys away from Coronis, and the colour has characterized all its descendants to this day.

Apollo knew that Coronis was already carrying his child. In a fit of rage, he picked up his bow to punish her for her betrayal. As soon as he had released the arrow he realized the folly of his action, but it was too late, for an arrow fired by a god can never miss its target. Guilt frequently precedes action in this way, being already present in the intention; the thinnest of threads prevents a thought from being immediately turned into action. When the tension becomes uncontrollable, the thread can release the accumulated energy, resulting in a rash act whose consequences are both unpredictable and irremediable.

Overcome with grief and remorse, Apollo ran to embrace the woman he still loved, and she died in his arms. To atone for his guilt, he laid her body on the funeral pyre, as ritual required; it was a heinous offence not to honour the dead. But as the fire burned, he cut from her womb the baby – his son Asclepius, the god of medicine.

Coronis’s fate was sealed by the violence of the male members of her family. Her fate illustrates femininity’s lack of autonomy with respect to an archaic male principle, and its coercion by that principle. The situation goes back far earlier than the events that culminated in Asclepius’s birth. The violent history of the menfolk of Coronis’s family links Asclepius’s human origins to the dark, fiery, hellish side of nature.

Asclepius’s mother came from a cursed lineage. Her father Phlegyas tried to burn down the temple of Apollo in Delphi. His name recalls the Greek verb phlego and the Latin verb flagro, both meaning ‘to set fire to’, or ‘to burn’. It is emblematic of sudden, blazing anger, a dark, smouldering fire that is always ready to flare up. His story would make him the perfect ferryman for the Styx in Dante’s Divine Comedy.

His son, Ixion, Coronis’s brother, killed his guest Deioneus in a particularly cruel manner, by tricking him into falling into a pit full of burning coals. Ixion tried to to rape Hera, the queen of the Gods, and was punished by being tied to one of the wheels of the sun’s chariot. His relationship with Nephele was said to have given rise to the race of the Centaurs.

The Centaurs themselves were subject to violent, uncontrolled outbursts of rage when drunk on wine. They represent the violence of the pre-paternal male group, whose characteristics are coercion and an animalesque, warlike inebriation unmitigated by any feminine charm. The only way the group can relate to women is through lust, possession and rape.[i] Significantly, a descendant of this line was the wise Chiron, himself a centaur, the first physician and Asclepius’s teacher.

Phlegyas and Ixion represent the destructive violence of fire, the untamed, terrifying nature of the pre-technological age, against which the human race struggled from prehistoric times until the discovery of fire and the first technological, or Promethean, era.[ii] According to Kerényi,[iii] Coronis’s husband Ischys represents Apollo’s ‘dark double’, and in particular his destructive side – the urge to destroy which is inherent in Asclepius’s genealogy. So the transformation of fire into the funeral pyre lit by Apollo’s love and repentance is striking. Asclepius is born from that fire. Apollo’s action, in snatching his son from his mother’s burning womb, suggests a paternal desire for reconciliation with a feminine principle of mercy and grace, in contrast to the violent, uncharitable nature of the male members of Coronis’s family. The father’s reparatory gesture brings forth a divine child, enriched by the events that had accompanied his conception and birth. Indeed, the child’s birth, according to Kerényi,[iv] was in fact a rebirth, in the sense that one side of Apollo’s nature emerged to replace another: a lethal power was transformed into a healing one. Later Asclepius’s hubris proved his downfall: he was burned to ashes by one of Zeus’s thunderbolts for daring to substitute his omnipotence for nature. Asclepius dies because he is unable to conquer the element – death – which characterizes not only his destiny but also his art and knowledge.

Symbolically these events shape Asclepius’s art of medicine. On the one hand he embodies the solar principle inherited from his father Apollo, the agent of life. On the other hand, paradoxically, he embodies the ‘hidden fire’ inherent in the violent potential of human nature – a fire that destroys, rather than providing light. But the ‘hidden fire’ also implies a possibility of redemption. It will cease to be hidden when Prometheus steals it from the gods and gives it to man. As a result, fire is transformed and tamed; it can be used by humankind, becoming an incarnation of techne in matter.

The Apollonian keenness of Asclepius’s gaze, according to Kerényi,[v] is tempered by a sadder, warmer tint – a tragic shade, suggesting affinities with Dionysus. Wine played an important part in ceremonial sacrifices to the ‘physician-god’, too. The proximity of the Asklepieion, or temple of Asclepius, to the theatre of Dionysus in Athens, and of the tomb of the heros iatros (health-bringing hero) to the shrine of Dionysus at Marathon, indicate a link between Asclepius and Dionysus. Asclepius is born from Coronis’s ashes, just as Dionysus is born from the ashes of Semele, daughter of Cadmus and Harmonia. Semele fell into a trap set by the jealous Hera. Pretending to be her friend, Hera instilled in her a desire to be united with Zeus in his divine form, knowing that this would result in her death. The king of the gods tried in vain to dissuade her, but eventually, compelled to do so by a promise, he appeared to her in all his splendour, burning her to ashes. This seems to be a metaphor for divine inebriation, and for the mad god who would be born. Zeus saved the child that Semele bore in her womb by sewing it into one of his thighs, where it completed its gestation.[vi]

Both Asclepius and Dionysus, then, are characterized by a special link, from birth, with the dimensions of fire and death; both are born from a dying, or ‘burning’, womb: in one case consumed by a human, earthly fire lit by the god, in the other burned to ashes by the fire inherent in Zeus’s divine nature. Dionysus, however, must continue to mature in his father’s thigh – he has not completed his gestation; unlike Asclepius, he is not yet completely ‘born’. The symbolic meaning of the link between these two gods and their cults will be discussed later.

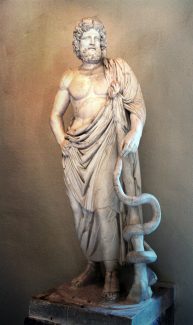

Asclepius possesses an innate sensibility that will develop into a knowledge of human suffering, in a borderland between life and death, represented by his symbolic animals, the serpent and the dog. They stand for the natural, chthonian and emotional aspects of the human being.

Sick people would spend a night in the temple, in the protected space of the temenos (‘sacred precinct’, from temno, to cut, split). The two animals would appear to them in a dream, in the likeness of handsome young men bearing the gift of healing. Sometimes the god himself would appear as a divine child. Illness was experienced as a process of initiation; after initial purification, the sick person would be sent into the sacred protected space inside the Asklepieion and there be bitten by the serpent, thus having a symbolic experience of death. This would be accompanied by a theophany, or encounter with the god in a dream. The person would be reborn into a human condition enriched with sensibility and knowledge because of the transition that had occurred – or, in psychological terms, because of their integration of an unconscious content.

Protected by the ritual container of tradition, individuals do not shrink from this experience, but participate in the process of healing, preserving their links to the vital energies (of the unconscious). They do not merely ‘undergo’, and are not merely ‘patients’ (from pathos, to suffer). So they are not absolutely distinct from a healthy person. On the contrary, the initiate / patient actively integrates both conscious and unconscious content , (re)constructing their identity in a fertile exchange with the temple / world outside. There is no clear distinction, but only a symbolic gradient, between health and sickness.

In our own time, this experience is subject to the principle of causality inherent in medical science. That science has to make appropriate changes to the process of the disease in order to achieve ‘recovery’. In the temenos, the experience becomes an inner experience situated on the threshold of the communicable, on a terrain different from that of science – namely the individual’s own capacity for symbolization. Individuals are not patients, but people who ‘incubate’ the possibility of their own evolution – that is, already contain that evolution within themselves, protecting it and cultivating it, by the intercession of the god. The outcome of that evolution is not ‘causally’ predetermined. In this sense there are similarities with the process of individuation, ‘becoming oneself’, which in analytical psychology takes the place of the clinical concept of healing.

In his Attempt at Self-Criticism, Nietzsche says of his Birth of Tragedy that it is ‘constructed of nought but precocious, unripened self-experiences, all of which lay close to the threshold of the communicable, based on the groundwork of art – for the problem of science cannot be discerned on the groundwork of science.’[vii]

In the same way it may be said of modern medicine that only by standing outside the field of clinical scientific reasoning can we hope to identify the underlying problem of medicine. If we do not include within our thinking a symbolic view, centred on our relationship with the patient, we lose the most significant dimension of the experience of illness, and the potential deriving from the patient’s particular world view (Weltanschauung). The Cartesian distinction between subject and object which underlies the principle of causality in scientific explanatory medicine leads us to express all knowledge according to the dictates of objectifying reason. This approach seems reductive, however, with respect to the psyche’s own way of knowing things, which operates on several different levels simultaneously – the rational, the emotional, the symbolic and the sensorial. However useful to science the distinction between subject and object, soul and body (or psyche and soma) may be, in the experience of major events like illness it becomes arbitrary. A transitional area is created in the patient’s inner experience – a far more vaguely defined and constantly changing area, but a crucially important one, for it expresses its particular dimension, the uniqueness of its limit and therefore the unrepeatability of its approach to death. This condition of liminality, which does not fall within the field of reality of every scientific hypothesis, can, if it is included and properly exploited in the patient’s relationship with the doctor, become a potential source of knowledge for both parties. In the temenos it lies at the centre of the therapeutic process.

[i] Zoja 2010, pp. 3-12 (Italian edition only).

[ii] Jaspers 1949, p. 24: ‘Four times man seems, as it were, to have started out from a new basis. First from prehistory, from the Promethean age that is scarcely accessible to us (genesis of speech, of tools and of the use of fire), through which he first became man. Secondly, from the establishment of the ancient civilisations. Thirdly, from the Axial Period through which, spiritually, he unfolded his full human potentialities. Fourthly, from the scientific-technological age, whose remoulding effects we are experiencing in ourselves.’

[iii] Kerényi 1948.

[iv] Ibidem.

[v] Ibidem.

[vi] Kerényi 1951, p. 257.

[vii] Nietzsche 1872, p. 3-4.

Published in the Research in Analytical Psychology and Jungian Studies Series

© 2018 – Routledge

Photography: Asclepius, with his serpent-entwined staff, Archaeological Museum of Epidaurus – © Michael F. Mehnert – Wikimedia Commons

“Modern Myths and Medical Consumerism considers medicine from a vast perspective, the author being an experienced cardiologist and an analyst with a cosmopolitan background. This clear and deep text analyzes the philosophical roots and archetypal history of medical omnipotence: no other essay has done it before. It is essential reading not only for psychotherapists, medical doctors and patients, but more broadly for anyone interested in the ever growing arrogance of Western technology.”

Luigi Zoja, author and former President of the International Jungian Association.

“With the inexorable rise in medical consumerism, and the concomitant increase in the tendency to deny the existence of death, there is an urgent need to examine why this is so. This elegantly composed monograph, written by a percipient cardiologist, is an incisive analysis of the topic. It is an admirable guide to all members of the lay public who are interested in modern-day trends in medical practice.”

Sir John Meurig Thomas, FRS, FREng, University of Cambridge.